Web Services Introduction

The goals of this short introduction are as follows:

Introduce the idea of a web service, and cover the relevant terminology

Explain the roles of the requestor (the client) and the responder (the server)

Discuss how a client uses an HTTP client object (e.g. XmlHttpRequest, or the fetch API) to contact a server, and handle (typically) JSON data responses

Promote the idea that we are building and working with a distributed computing system, that has two or more autonomous programs that pass messages (requests, responses) among the programs

What is a web service?

A web service is an application that runs on a web server, and is accessed programmatically.

When we parse this short sentence, and consider the meanings behind the simple words, we reveal some very important concepts:

- HTTP is the protocol, enabling wide use and scalability

- Humans don't use a web service directly - instead, the application they are using creates and sends a request to the web service, and handles the response in a way that's meaningful to the application

- A web service's functionality is discoverable, and typically known as an application programming interface (API)

Web services can be developed on any web-connected technology platform, in any language, and can be used on any kind of device.

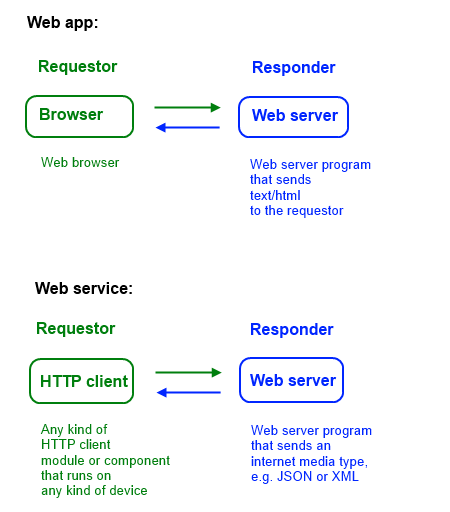

What's the difference between a web app, and a web service?

Study this diagram to understand the differences, and then be prepared to explain them to someone else:

Give me a brief history lesson on web services

With the rise of the web's use and popularity in the 1990s, efforts were made to define and specify web services.

This led to the de facto standardization of SOAP XML web services. Often described as "big web services", or "legacy web services", SOAP XML web services are the implementation of remote procedure calls on the web. This kind of web service typically has one specific endpoint address, and requestors must create and send a data package (which conforms to a data format named SOAP), and then process the response (which also conforms to SOAP).

However, other efforts took advantage of the web and its existing features and benefits. In other words, they simply followed the HTTP specification and its ex post facto architecture definition, to create true and pure web services. These kinds of web services, often termed "Web API", "RESTful web services", or "HTTP services", exploded in use and popularity from about 2005 onwards, and are now the preferred design approach.

Web services development and deployment environment

This course will use the following frameworks and tools:

- Node.js

- Express.js

- MongoDB

- Visual Studio Code

Each web service that you create will be treated as a separate and distinct program, and not bundled in with the front end client (browser) app that you may be working on. It will be concerned only with listening then responding to requests that come in.

During development, you will use an HTTP inspector app, like Thunder Client, to create and send requests to a web service.

Then, you will be creating separate web app clients, which send requests to your web service.

Each program can be individually and separately deployed to any device platform that meets your needs.

Terminology

As your web programming competency grows, it is important to know and be able to correctly use some common web programming terms.

Web app, and web service

If you create a server-based program, and it is intended to be used mostly by web browsers, we typically call that a web app.

Alternatively, if you create a server-based program, and it is intended to be used programmatically (by iOS and Android apps, or by JavaScript in a browser, or by an "HTTP client" module in a native Windows, macOS, or Linux app, we typically call that a web service.

Resource

A resource is a digital asset.

Familiar examples include a document, or an image.

How do you identify a resource? By using its URI (uniform resource identifier). The URI standard is described in RFC 3986, and also in a Wikipedia article.

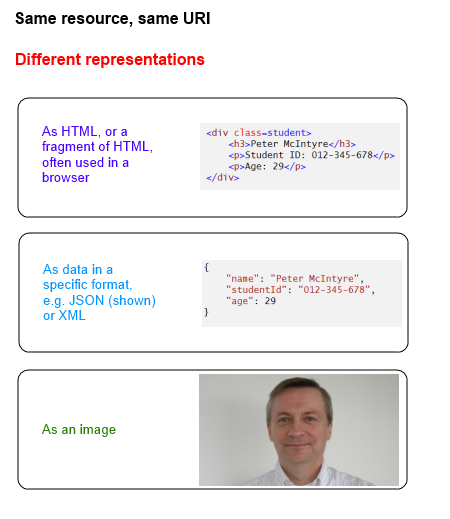

What is the format, or representation, of the resource? Well, it depends on the design of the web service, and sometimes the needs of the requestor.

Representation

As defined above, a resource is a digital asset.

A representation is a digital asset that is formatted as a specific internet media type.

The concrete or real form of a representation "is a sequence of bytes, plus ... metadata to describe those bytes".

From Roy Fielding, "Architectural Styles and the Design of Network-based Software Architectures", section 5.2.1.2

Think about a scenario where a web service was used to manage students in a course. Each student is a resource - a digital asset - that can be identified by a URI.

If a user requested a specific resource through a web browser, you would expect that the resource would be represented by some HTML that included the student's name, student ID, and so on.

Alternatively, it's also possible to request the same specific resource - using the same URI - but also specify that it be returned in a data format (like JSON or XML, discussed later). The server will return a data representation of the resource.

Or, maybe the request specified that the student's photo be returned as the resource's representation. Again, the same URI is used.

So, in summary, a resource's representation can vary to meet the needs of the web service programmer or the web service user. The requestor and responder use a feature called content negotiation to make this happen.

Every representation is defined by an internet media type.

Internet media type

An internet media type is defined as a data format for a representation of a resource on the internet.

The data formats are standardized, published, and well-known, by the IANA (the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority).

This Wikipedia article is an acceptable introduction to internet media types.

For web service programmers, two important internet media types are used as data formats, JSON and XML.

Both are plain-text data formats. They are somewhat human-readable.

Later, you will probably learn how to work with non-text media types. From now on, we will typically work with plain-text JSON.

Get started with JSON

JSON is an initialism for JavaScript Object Notation.

It is a lightweight data-interchange format. It is language-independent, however it uses conventions that were first suggested by the JavaScript object literal or initializer. JSON has become the de facto data-interchange format standard.

Here's an overview of JSON from Wikipedia.

Here's the official web site for JSON, by Douglas Crockford.

Although JSON is historically derived from JavaScript object literals, there are a few notable differences to programmers who are new to JSON:

In JSON, each property name must be surrounded by quotes (typically double-quotes). In pure JavaScript, this is optional for single-word property names.

In JSON, there is no Date type. Dates are expressed as strings, almost always in ISO 8601 format. In contrast, JavaScript does have a Date object (not a type, but an object).

While we're on the topic of data types, the property values will be any of about five types:

- string

- number (integer or decimal)

- object (i.e. { } )

- array (i.e. [ ] )

- null

String values must be surrounded by quotes.

The web services that you create in this course will rely on the JSON internet media type.

State

Let's discuss state in this section of the notes, and in the next section.

Data

In this section, we are interested in the state of the data elements in a distributed system. (In the next section, we will be interested in the state of the interaction among programs in a distributed system.)

In a web app or web service context, the meaning of the word state is the current value of a resource.

At the server, a resource could be in the form of an item in a persistent store (i.e. a database system), or it could be in the form of an item that is generated upon request. That difference doesn't matter; what matters is that when a resource is requested, its current state is sent, or transferred, as the response.

A resource's state can be changed (or modified), of course. The stimulus for the change can originate from anywhere in the distributed system, ranging from server-based batch or automatic processes that modify the persistent store (apart from or separately from the web app or web service), through to client-sent requests that are received by a web app or web service.

Does this work the other way, when a client app changes the state of an resource?

Yes.

A client can send a request that includes a representation of a resource. (For example, an HTTP POST or PUT request.)

The new or updated state of the resource is transferred, from the client app to the server (web app or web service).

Upon acceptance (and validation etc.), the server appends to or updates the resource in the persistent store.

Interaction

In this section, we are interested in the state of the interaction among programs in a distributed system. (In the previous section, we were interested in the state of the data elements in a distributed system.)

One of the characteristics of a web app or web service is that it can be used by a single client app, or by theoretically unlimited numbers of client apps.

Does the server keep track of the interaction state with each client? No. This responsibility is borne by the client app. This design feature is one of most important parts of the web.

"Each request from client to server must contain all of the information necessary to understand the request, and cannot take advantage of any stored context on the server. Session state is kept entirely on the client." (Roy Fielding, PhD thesis, section 3.4.3)

The main point is that the server effectively treats every request as separate/discrete/atomic, and does not actively maintain any notion of a logical session over time. In other words, no interaction state maintenance or management is done at the server.

Therefore, if the interaction state of a (message exchange) session is important to maintain, it's done by the client.

REST

Now we can circle back to REST. It is an acronym for REpresentational State Transfer.

The implementation / description of a "REST API" can be simply described "as a way to use the HTTP protocol with a standard message format to perform operations on data". However, while that explanation is clear and understandable when first learning about REST, it embeds a much deeper understanding that can come only through more learning and experience. If a student is serious about a career that includes web programming, then it is essential to study Roy Fielding's PhD dissertation from the year 2000, Architectural Styles and the Design of Network-based Software Architectures.

More information about Roy Fielding is here.

Will we be creating "REST APIs"? Yes, if we follow all the guidance and practices. However, that will come only with more knowledge and experience.

As a result, it may be more accurate and safer to use the term "web API" when naming or describing our web service work.

Web API

The term "web API" captures the essence of "REST API" above, but it uses a more generic and easier to understand or explain word. Arguably, every computer user has a reasonably accurate knowledge of the word "web", so that word doesn't have to be explained. The expansion of the "API" initialism is also easy to understand or explain. It's just a bit better (and safer) than using "REST", and avoids the immediate need to cover large chunks of a 180-page PhD dissertation.

So, let's define "web API" as an API to a web app or web service.

In summary

In this document, we have defined and explained a web service.

Terminology was introduced, argued, and explained.

Now, you're ready to take the next step, and create web services that support the main focus of this course, which is front end client-side browser apps.